NILOY RAFIQ

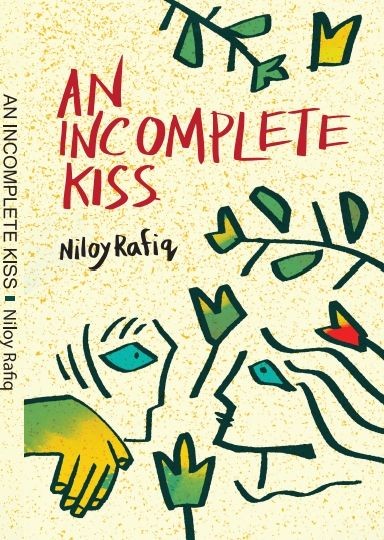

Un'Odissea Lirica tra Memoria e Resistenza: Recensione di An Incomplete Kiss

di Niloy Rafiq di Gausur Rahman

Traduzione in italiano a cura della redazione di SATURNO magazine

"An Incomplete Kiss" di Niloy Rafiq emerge come una costellazione luminosa di brillantezza poetica, intrecciando un ricco arazzo di sensibilità bengalesi con temi universali come la memoria, la resistenza socio-politica e una profonda comunione con il mondo naturale. La raccolta tradotta rivela un poeta di grande profondità, la cui voce lirica naviga tra le complessità dell’esperienza umana con tenerezza e ferocia.

Sebbene le traduzioni, a tratti, inciampino in imprecisioni grammaticali e formulazioni goffe che affievoliscono la forza dell’intento originario di Rafiq, la sua poesia riesce comunque a brillare, offrendo ai lettori un viaggio trascendente tra desiderio, ribellione e estasi spirituale.

Al centro dell’opera c’è una toccante esplorazione della memoria, spesso carica di un doloroso senso di incompletezza che supera i confini culturali. Nel componimento titolare An Incomplete Kiss, i versi «Le parole sono piatte sulla copertina della memoria / Dove restano i segni dei baci incompleti» incarnano un desiderio di pienezza, un motivo che attraversa l’intera raccolta.

Allo stesso modo, The Nose Pendant evoca la nostalgia con «Aprendo gli occhi, cerco ancora il ciondolo / Dietro le nuvole, nella copertina della mia memoria», dove il ciondolo simboleggia un legame culturale perduto, avvolto nel velo del ricordo. Gone Elsewhere approfondisce questo tema con «Tratta dall’ombelico, la bellezza è andata via altrove / La mappa trema d’inverno con il canto degli uccelli», dove la mappa tremante suggerisce una dislocazione dell’identità.

Va notato che l’espressione “è andata via altrove” risulta ridondante—una resa più corretta sarebbe “è andata altrove”.

L’immaginario sensoriale in «Raccolgo ostriche dalla riva del mare / Felicità eterna, attratta dalla terra» infonde alla poesia un desiderio tattile, anche se “riva del mare” andrebbe reso in modo più naturale con “spiaggia”. My Heart Aches For You approfondisce il tema con «Il cuore sognante risuona con il canto: / “Il mio cuore soffre per te!”», dove la sofferenza è tanto personale quanto cosmica, come mostra «La brezza del sud cancella le polveri di innumerevoli stelle». Il plurale “polveri” sarebbe da evitare—“polvere” come sostantivo non numerabile è più adatto.

An Apple Afternoon prosegue con «Dentro una borsa segreta, divorziata, in città / Un bel mercante sciocco tesse sogni», suggerendo una memoria frammentata. Tuttavia, “borsa segreta, divorziata” resta una formulazione ambigua, probabilmente legata a una metafora bengalese più delicata e difficile da tradurre.

Questa ossessione per la memoria si intreccia con una potente riflessione socio-politica, resa in modo particolarmente incisivo nel componimento The Burning Torch, dove i versi «Persone in lettere bruciate sulle strade di Chicago / Diciotto o venti ore di lavoro, / Il lavoro succhia il sangue dal corpo» restituiscono il tributo viscerale imposto dallo sfruttamento.

Il grido collettivo «Una voce fragrante e unita invoca un movimento per reclamare i diritti / Proiettili sulla marcia dei coraggiosi» giustappone speranza e violenza, culminando in «Una torcia di luce nella memorabile storia del Primo Maggio».

Tuttavia, l’espressione Victory Lamp, nella frase «Il raccolto della fatica nelle mani della Lampada della Vittoria», risulta goffa e poco chiara, mancando di un articolo definito o di una metafora più esplicita, spezzando il ritmo.

Il componimento Unaddressed amplifica questa critica: «Il frastuono delle nuvole sugli argini del destino / L’anima morta si risveglia sulla riva dell’ignoranza», evocando una disorientazione collettiva. Anche qui, la frase «si risveglia sulla riva» è più precisa rispetto alla versione originale.

In Mathin’s Victory, emerge una narrazione di resilienza: «Dhiraj è scritto nella storia con occhi ingannevoli / La vittoria di Mathin nel morire di fame» — una celebrazione tragica del sacrificio. Gli “occhi ingannevoli” restano ambigui e potrebbero beneficiare di un contesto più delineato.

The Blind Light offre una cruda allegoria politica: «L’habitat dei pescatori è un vuoto e il mare è proibito / La scarsità si posa felicemente mentre / Il magazzino del cibo è in fiamme», evidenziando la privazione sistemica. La frase “si posa felicemente mentre” sarebbe più fluida come “si posa felicemente mentre che” o “si posa felicemente come” per maggiore chiarezza.

The Saltpit risuona come eco della perdita ambientale e culturale: «Il suolo ritroverà mai il letto di semi perduto? / Siccità nella propria separazione, gli alberi giocano a nascondino», dove manca una preposizione: “gli alberi del nascondino” o “gli alberi che giocano a nascondino” renderebbero più chiaro il messaggio.

L'affinità di Rafiq con la natura e la spiritualità, marchio distintivo della poesia bengalese, permea le sue opere con una reverenza quasi tagoriana. Clouds In Front ci regala immagini celesti: «Il sole primaverile vola, la marea è alta / Le ali del corpo si intrecciano con la scriminatura del cielo», fondendo terra e divino. In questo contesto, “si intrecciano” è una resa più fluida di “sono incarnate”.

Il mitico Pulsirat, il fiume dei morti, aggiunge profondità simbolica, anche se la resa letterale di “la scriminatura dei cieli” offusca la potenza dell’immagine originale.

Gone Elsewhere riprende questo tono con «La nebbia fitta rende il ciclo della vita un disastro / La futura vittoria conta il tempo con il profumo dei girasoli», dove gli errori di trascrizione “makesthe” e “victorycounts” denotano trascuratezza — andrebbero corretti in “makes the” e “victory counts”.

The Ribs of Chest approfondisce il tema con «La vecchia casa di fango è uno scorcio di vita industriale / Le parole sono rami profumati degli alberi seminanti», anche se l’espressione “roots re divided” è evidentemente un refuso — probabilmente “roots are divided”.

The Dream Drunkard introduce una dimensione mistica con «Il vino ambrosiano di Rumi è nella foresta degli uccelli / Il tempo si ferma sul calesse al crocevia di Jhautla», evocando il poeta sufi Rumi. Tuttavia, “ambrosiac” è un aggettivo inusuale — “ambrosial” sarebbe più adatto.

Il verso «Il volto della nuvola è un veleno segreto» contiene un errore grammaticale — “nuvola” dovrebbe essere al plurale o preceduta da “la”: “Il volto della nuvola” rende l’immagine più chiara.

The Saltpit genera un legame viscerale con la natura: «L’infatuazione del sole come un fiume di ninfee chiude la vita / Il corpo avvolto da un tappeto freddo», ma l’espressione “chiude la vita” (da “lifetime end”) suona goffa — forse si intendeva “la fine della vita”.

An Apple Afternoon evoca immagini surreali: «I fiori sbocciano come ombre nello spazio ignoto; / L’anima è morta, la linea della vita è una processione di carri», dove la maiuscola “The” è usata in modo incoerente — segno di un errore editoriale.

Stilisticamente, Rafiq impiega immagini dense, evocative, con una cadenza ritmica che richiama le tradizioni orali. Metafore come “il sorriso della moneta d’oro” in An Incomplete Kiss o “voce fragrante e unita” in The Burning Torch arricchiscono il testo — anche se le traduzioni, a tratti, inciampano.

In The Nose Pendant, il verso «Due artisti si trovano faccia a faccia su una mappa antica» è privo di preposizione — “che si fronteggiano” renderebbe il significato più chiaro.

Unaddressed introduce «Una farsa di palloncini nel flusso del tempo», dove “trickery” è singolare e manca di accordo con “balloon” — una resa più precisa potrebbe essere “farse con i palloncini”.

La frase «Chi egli stesso non sa nemmeno dove sia l’indirizzo!» usa “egli stesso” in modo ridondante — una versione più elegante sarebbe: “Chi non sa nemmeno dove si trovi l’indirizzo.”

My Heart Aches For You propone «Disegna finestre d’acqua con i pennelli del suono», ma “finestre d’acqua” resta ambiguo — forse si intendeva “finestre acquose” o “finestre immerse nell’acqua”.

Mathin’s Victory offre «L’acqua diventò blu e rosso sangue!» — dove il punto esclamativo appare forzato, e “rosso sangue” andrebbe reso come “rosso-sangue” per correttezza grammaticale.

In The Saltpit, il verso «Luce e ombra, particelle di sabbia, mare silenzioso!» è privo di punteggiatura — una disposizione più chiara rafforza l’immagine.

Infine, The Blind Light presenta «Puoi vedere tet è una luce cieca in una città di muti» — dove “tet” è un errore tipografico per “that”, e “mutes” dovrebbe essere “i muti” per correttezza.

An Apple Afternoon conclude con «I tamarischi salati sono avvolti nel suono sotto un manto di luce / Il villaggio dorato delle radici è ambrosia al suo interno» — dove l’uso di “ambrosia” come sostantivo è poco fluido, forse “essenza ambrosiale” renderebbe meglio la metafora.

La specificità culturale, evidente nei riferimenti al “vecchio fiume Brahmaputra”, a “Krishnachura Road” o al “crocevia di Jhautla”, ancora profondamente la poesia in un contesto bengalese, ma rischia di allontanare i lettori privi di conoscenze locali. Nel testo An Incomplete Kiss, il verso «Il vecchio fiume Brahmaputra chi chiama?» utilizza impropriamente “chi” in forma arcaica — sarebbe più corretto “chi sta chiamando?”.

In Gone Elsewhere, l’espressione «Che l’immortale albero sbocci in una luce brillante» è affetta da un errore tipografico (“treeblossom” invece di “tree blossom”) e manca di articolo definito. Mathin’s Victory cita “Patuar Tek”, probabile località bengalese, ma senza annotazione il suo significato rimane opaco. The Saltpit con «Fragranza della tradizione, l’artigiano tra le nuvole nere / Odore di terra nel cuore, e acqua alle radici rifugiate!» crea suggestioni evocative, ma una congiunzione rafforzerebbe la coerenza.

Nonostante queste imperfezioni, la voce di Rafiq brilla, fondendo bellezza lirica e consapevolezza sociale. The Ribs of Chest esplora la tensione tra eredità e divisione, anche se “dialoghi nell’assassino oscuro” è grammaticalmente incoerente — probabilmente si intendeva “dialoghi con un assassino oscuro”. Unaddressed con «Immerso in una preghiera nel palazzo dei fiori / Un canto di inni sulla soglia della morte» evoca un viaggio spirituale profondo. La frase «La portantina di nuvole è sotto la tempesta» sarebbe più chiara resa come “al di sotto della tempesta”.

The Dream Drunkard con «Disegna cerchi d’acqua, la luce degli uccelli sulla via verso le stelle» è visivamente potente ma stilisticamente goffa — una versione migliorata potrebbe essere: «Disegnando cerchi d’acqua, la luce degli uccelli guida la via verso le stelle». The Blind Light presenta «La volpe astuta ruba i pesci hilsa dentro le costole» — “fishes” è un uso ridondante; “fish” basterebbe secondo la grammatica standard.

Oltre le critiche, la poesia di Rafiq si impone con una brillantezza effervescente che eleva An Incomplete Kiss a un’opera d’arte senza tempo, testimone della sua padronanza linguistica ed emotiva. La sua capacità di distillare l’ineffabile — il dolore di un bacio mai compiuto o il grido collettivo per la giustizia — in immagini cristalline è pura maestria. In The Burning Torch, la trasformazione della sofferenza del lavoro in «Una torcia di luce nella memorabile storia del Primo Maggio» dimostra la sua abilità nell’alchemizzare il dolore in speranza, in linea con la grande tradizione della poesia di resistenza globale.

L’equilibrio delicato tra natura e spiritualità in Clouds In Front, con «Il sole primaverile vola, la marea è alta», evoca una danza cosmica che supera ogni confine culturale. Unaddressed amplifica questo, con «Un canto di inni alla porta della morte» — una meditazione struggente sulla mortalità, dove spirituale e materiale convergono in sublime chiarezza. The Dream Drunkard incanta con «Una frenesia di musica riverbera al crocevia di Jhautla», tessendo un incantesimo che riecheggia il lascito mistico di Rumi.

My Heart Aches For You cattura un tenero desiderio con «Quanto è rapita la marea dai clamori esultanti!» — nonostante l’errore (“Howrapt”), il verso pulsa di autenticità emotiva. Mathin’s Victory celebra la resilienza con «I sentieri alti e bassi sono la fragranza dell’amore», una metafora che racchiude la capacità di Rafiq di trovare bellezza nella lotta. The Saltpit ipnotizza con «Saline nebbiose, una fiera di fulmini», immagine che trasforma la desolazione in spettacolo naturale. The Blind Light con «La storia della vita è un pendolo di ballate sognanti» offre una riflessione filosofica sull’esistenza, fondendo il ciclico con il lirico. An Apple Afternoon chiude con delicatezza: «La strada è aperta, fin dove puoi andare / Cercherò un pomeriggio di mela sul mio palmo» — una promessa di speranza, dove “il pomeriggio di mela” diventa simbolo di rinascita nella disperazione.

Le metafore di Rafiq — come “il sorriso della moneta d’oro” o “i rami profumati degli alberi seminanti” — non sono semplici ornamenti, ma rivelazioni. Ogni poesia è un mosaico delicato, ogni parola una scheggia di luce che rifrange la complessità dell’anima umana. Dal dolore quieto di The Nose Pendant alla sfida ardente di The Burning Torch, Rafiq si rivela come un bardo versatile, un tessitore di sogni le cui visioni sono tanto eterne quanto i fiumi e i cieli che evoca.

An Incomplete Kiss è la prova del talento di Rafiq nel navigare il personale e il collettivo, il locale e l’universale, con una sensibilità distintamente bengalese. La profondità tematica — memoria, resistenza, natura — offre un’esperienza poetica intensa. Le imperfezioni grammaticali (come “makesthe”, “re divided”, “be perished”) e le frasi poco fluide (“heaven’s hair-parting”, “Victory Lamp”) ostacolano il flusso, ma per chi è disposto a immergersi nelle sue sfumature culturali, questa raccolta rimane una riflessione struggente sull’esistenza umana, elevata dal genio poetico di Rafiq. Una traduzione più accurata sarebbe essenziale per onorare appieno la sua visione.

A Lyrical Odyssey Through Memory and Resistance: A Review of Niloy Rafiq’s An Incomplete Kiss

Gausur Rahman

Niloy Rafiq’s “An Incomplete Kiss” emerges as a luminous constellation of poetic brilliance, weaving a rich tapestry of Bengali sensibilities with universal themes of memory, socio-political resistance, and a profound communion with the natural world. The translated collection reveals a poet of depth, whose lyrical voice navigates the intricacies of human experience with both tenderness and ferocity. While the translations occasionally falter, encumbered by grammatical inaccuracies and awkward phrasing that dilute the resonance of Rafiq’s original intent, the poet’s poetry shines through, offering readers a transcendent journey through longing, rebellion, and spiritual reverie.

At the heart of Rafiq’s poetry lies a poignant engagement with memory, often imbued with an aching sense of incompleteness that resonates across cultural boundaries. In the titular “An Incomplete Kiss,” the lines “The words are flat in the cover of memory / Where the marks of incomplete kisses are left” encapsulate a yearning for wholeness, a motif that reverberates through the collection.

Similarly, “The Nose Pendant” evokes nostalgia with “Opening my eyes, I search still the nose pendant / Behind the clouds, in the cover of my memory,” where the pendant symbolizes a lost cultural tether, shrouded in recollection’s haze. “Gone Elsewhere” extends this theme, as seen in “Drawn by the navel, the beauty has gone away elsewhere / The map shivers in winter with the song of birds,” where the shivering map suggests a dislocation of identity.

However, the phrase “has gone away elsewhere” is grammatically redundant—correctly rendered as “has gone elsewhere” would suffice.

The sensory imagery of “I collect oysters from the sea shore / Everlasting happiness, being drawn by the earth” infuses the poem with tactile longing, yet “sea shore” should be “seashore” for grammatical consistency. “My Heart Aches For You” deepens this theme with “The dreamy heart rings with the song: / ‘My heart aches for you!’” where the ache is both personal and cosmic, mirrored by “Southern breeze wipes out the dusts of innumerable stars.” The plural “dusts” is incorrect—“dust” as an uncountable noun would be appropriate. “An Apple Afternoon” further explores this with “Inside a divorced secret purse in the city / A handsome dunce merchant weaves dreams,” suggesting a fragmented memory, though “divorced secret purse” feels awkward, potentially a mistranslation of a more nuanced Bengali metaphor.

This preoccupation with memory intertwines with socio-political commentary, most strikingly in “The Burning Torch,” where “People in burnt letters on the Chicago streets / Eighteen or twenty working hours, / Labour sucks blood from body” portrays the visceral toll of exploitation. The rallying cry, “A fragrantly united voice calls for a movement demanding the dues / Bullets to the brave march,” juxtaposes hope with violence, culminating in “A torch of light in the memorable history of May Day.”

Yet, the phrase “Victory Lamp” in “The harvest of hard work in the hands of Victory Lamp” is awkwardly phrased, lacking a definite article or clearer metaphor, disrupting the rhythm. “Unaddressed” complements this critique with “The clamour of clouds on the banks of destiny / The dead soul wakes up in the shore of ignorance,” suggesting collective disorientation, though “wakes up in the shore” should be “wakes on the shore” for precision. “Mathin’s Victory” introduces a narrative of resilience with “Dhiraj is written in history with deceitful eyes / Mathin’s victory in starving to death,” portraying a triumph born of suffering, though “deceitful eyes” feels ambiguous, and the phrase might benefit from clearer context. “The Blind Light” offers a stark socio-political allegory with “The habitat of fishermen is a void and the sea is forbidden / The scarcity sets happily while / The warehouse of food is on fire,” addressing systemic deprivation, though “sets happily while” is grammatically awkward—correctly “sets happily as” would improve clarity perfectly. “The Saltpit” echoes this with “Will the soil get back the lost seedbed? / Drought in its own separation the hide and seek trees,” a metaphor for environmental and cultural loss, though “the hide and seek trees” lacks a preposition, correctly “the hide-and-seek trees.”

Rafiq’s affinity for nature and spirituality, a hallmark of Bengali poetry, permeates his work with a Tagorean reverence. “Clouds In Front” offers celestial imagery in “The spring sun is flying, the tide is high / The wings of the body are embodied in the heaven’s hair-parting,” blending the earthly with the divine, though “are embodied” is redundant—“are entwined” would enhance flow.

The mythological “Pulsirat, the river of the dead” adds depth, yet the literal “heaven’s hair-parting” obscures the original metaphor. “Gone Elsewhere” echoes this with “Heavy fog makesthe life cycle a disaster / The future victorycounts time by the scent of sunflowers,” where “makesthe” and “victorycounts” are typographical errors, correctly “makes the” and “victory counts,” reflecting careless transcription. “The Ribs of Chest” further enhance this theme with “The old mud house is a glimpse of the industrial life / The words are the scented branches of the seed-bearing trees,” though “roots re divided” is a misprint, likely “roots are divided.”

“The Dream Drunkard” introduces a mystical dimension with “Rumi’s ambrosiac wine is in the forest of birds / Time stands still on the carriage in the Jhautla crossing,” invoking the Sufi poet Rumi, though “ambrosiac” is a questionable adjective—“ambrosial” would be more fitting. The line “The countenance of cloud is a secret poison” contains a grammatical error, as “cloud” should be plural or preceded by “the,” correctly “The countenance of the cloud.” “The Saltpit” brings a visceral connection to nature with “The infatuation of the sun like a water lily river lifetime end / The body wrapped with a cold mat,” though “lifetime end” is awkwardly phrased—perhaps “life’s end” was intended. “An Apple Afternoon” evokes a surreal natural imagery with “Flowers bloom like shadows in the unknown space; / The soul is dead, The life line is a procession of chariots,” where the capitalization of “The” is inconsistent, suggesting an editorial oversight.

Stylistically, Rafiq employs dense, evocative imagery and a rhythmic cadence reminiscent of oral traditions. Metaphors like the “gold coin smile” in “An Incomplete Kiss” or the “fragrantly united voice” in “The Burning Torch” enrich the text, yet translations falter. In “The Nose Pendant,” “Two artists are face to face on an ancient map” lacks a preposition, such as “facing each other,” rendering it vague. “Unaddressed” introduces “A trickery of balloon in the stream of time,” where “trickery” is singular but lacks agreement with “balloon,” suggesting “trickeries” or “a trickery with balloons.” The line “Who himself does not even know where the address is!” uses “himself” redundantly—“Who does not even know where the address lies” would be more elegant.

“My Heart Aches For You” presents “Draw water windows with the brushes of sounds,” where “water windows” is ambiguous and possibly a mistranslation, potentially intending “watery windows” or “windows of water.” “Mathin’s Victory” includes “The water turned blue and blood red!” where the exclamation feels forced, and “blood red” should be hyphenated as “blood-red” for grammatical correctness. “The Saltpit”’s “Light and shadow sand particles silent sea!” is a run-on phrase lacking punctuation—“Light and shadow, sand particles, silent sea!” would provide clarity. “The Blind Light”’s “You can see tet it’s a blind light in a city of dumbs” contains a typographical error, “tet” instead of “that,” and “dumbs” should be “the dumb” for grammatical accuracy. “An Apple Afternoon”’s “Salty tamarisks are wrapped in sound under a cover of light / Golden village of the root is an ambrosia inside” uses “ambrosia” as a noun but feels awkward—perhaps “ambrosial essence” would better capture the intended metaphor.

Cultural specificity, evident in references like the “Old Brahmaputra river,” “Krishnachura Road,” or “Jhautla crossing,” grounds the poetry in a Bengali milieu, yet may alienate readers without context. In “An Incomplete Kiss,” “The Old Brahmaputra river calls whom?” employs the archaic “whom” incorrectly—“who” would be appropriate in this case. “Gone Elsewhere”’s “May the immortal treeblossom in a bright light” contains a typographical error, “treeblossom” instead of “tree blossom,” and lacks an article, correctly “May the immortal tree blossom in a bright light.” “Mathin’s Victory” references “Patuar Tek,” a likely Bengali locale, but without annotation, its significance remains obscure. “The Saltpit”’s “Fragrance of tradition the craftsman in the black clouds / Smell of soil in the heart and water the refugee roots!” is evocative but grammatically disjointed—adding a conjunction, “Fragrance of tradition, the craftsman in the black clouds, / Smell of soil in the heart, and water, the refugee roots!” would improve coherence. The absence of contextual notes exacerbates this opacity, a missed opportunity to bridge cultural gaps.

Despite these flaws, Rafiq’s voice shines through, blending lyrical beauty with social awareness. “The Ribs of Chest” captures heritage’s tension with division, though “dialogues in the dark assassin” is grammatically incoherent, possibly intending “dialogues with a dark assassin.” “Unaddressed”’s “Immersed in a prayer in the palace of flowers / A chant of hymns at the door of death” evokes a spiritual journey, yet “palanquin of clouds is under the storm” should be “the palanquin of clouds is beneath the storm” for clarity. “The Dream Drunkard”’s “Draws water circles, the light of birds on the way to the stars” is poetically striking but grammatically awkward—“Drawing water circles, the light of birds guides the way to the stars” would enhance clarity. “The Blind Light”’s “The cunning fox steals hilsa fishes inside the ribs” uses “fishes” redundantly—“fish” would suffice, aligning with standard English usage.

Beyond these critiques, Rafiq’s poetry commands an effervescent brilliance that elevates “An Incomplete Kiss” to a realm of timeless artistry, a testament to his mastery of language and emotion. His ability to distill the ineffable—whether the ache of an unfulfilled kiss or the collective cry for justice—into crystalline imagery is nothing short of masterful. In “The Burning Torch,” the transformation of labor’s suffering into “A torch of light in the memorable history of May Day” is a testament to Rafiq’s skill in alchemizing pain into hope, a feat that resonates with the global canon of resistance poetry.

The delicate interplay of nature and spirituality in “Clouds In Front,” where “The spring sun is flying, the tide is high,” evokes a cosmic dance that transcends cultural boundaries, inviting readers into a pantheistic embrace that feels both ancient and eternal. “Unaddressed” further exemplifies this, with “A chant of hymns at the door of death” offering a hauntingly beautiful meditation on

mortality, where the spiritual and material converge in a moment of sublime clarity. “The Dream Drunkard” enchants with “A frenzy of music is reverberating in the Jhautla crossing,” weaving a spell of intoxication that mirrors Rumi’s mystical legacy, while “My Heart Aches For You” captures a tender longing in “Howrapt the sea is with elated uproars!”—a line that, despite its grammatical error (“Howrapt” should be “How rapt”), pulses with emotional authenticity. “Mathin’s Victory” celebrates resilience with “The high and low routes are the fragrance of love,” a metaphor that encapsulates Rafiq’s ability to find beauty amidst struggle. “The Saltpit” mesmerizes with “Misty saltpits a fair of lightning,” a vivid image that transforms desolation into a spectacle of nature’s power, while “The Blind Light”’s “The life story is a pendulum of dreamful ballad” offers a philosophical reflection on existence, blending the cyclical with the lyrical. “An Apple Afternoon”’s “The road is open, as far as you can go / I’ll search out an apple afternoon on my palm” is a tender promise of hope, where the “apple afternoon” becomes a symbol of renewal amidst despair.

Rafiq’s metaphors—the “gold coin smile,” the “scented branches of the seed-bearing trees”—are not merely decorative but revelatory, peeling back layers of human experience to reveal truths that linger long after the page is turned. His work, even through the veil of imperfect translation, radiates a luminous authenticity, positioning him as a poet of profound emotional and intellectual depth, whose verses deserve a place among the luminaries of modern poetry. Each poem in this collection is a delicate mosaic, where every word is a shard of light, refracting the complexities of the human soul with a grace that is both ethereal and grounded. Rafiq’s ability to traverse the spectrum of human emotion—from the quiet despair of “The Nose Pendant” to the fiery defiance of “The Burning Torch”—marks him as a bard of versatility, a weaver of dreams whose verses are as timeless as the rivers and skies he so vividly invokes.

“An Incomplete Kiss” is a testament to Rafiq’s ability to navigate the personal and collective, the local and universal, with a distinctly Bengali sensibility. The thematic depth—memory, resistance, and nature—offers a rewarding exploration, yet the translations are hindered by grammatical errors like “makesthe,” “re divided,” and “be perished,” alongside awkward phrasing such as “heaven’s hair-parting” and “Victory Lamp.” For readers willing to engage with its cultural nuances, the collection remains a poignant reflection of human experience, elevated by Rafiq’s poetic genius, though a refined translation would better honor his vision.